Universities are following the real estate model of their professional sport counterparts.

The Big House. The Swamp. Death Valley. All iconic names for classic stadiums that add to the legend of college football. But in the current era, these large facilities have to drive more than memories to meet the increasing revenue demands of Division I athletics. Having such a large chunk of real estate that depends on six home games a year for the bulk of its revenue is an underperforming asset. That’s why universities are taking a page from their professional sport counterparts in exploring new ways to monetize their facilities.

Taking up the model set by The Battery in Atlanta, universities are quickly transforming single-use sports venues to multi-purpose event sites, and even to entertainment districts that can generate revenue every day of the year. College policies and campuses are being reshaped by this trend across the country, including the following:

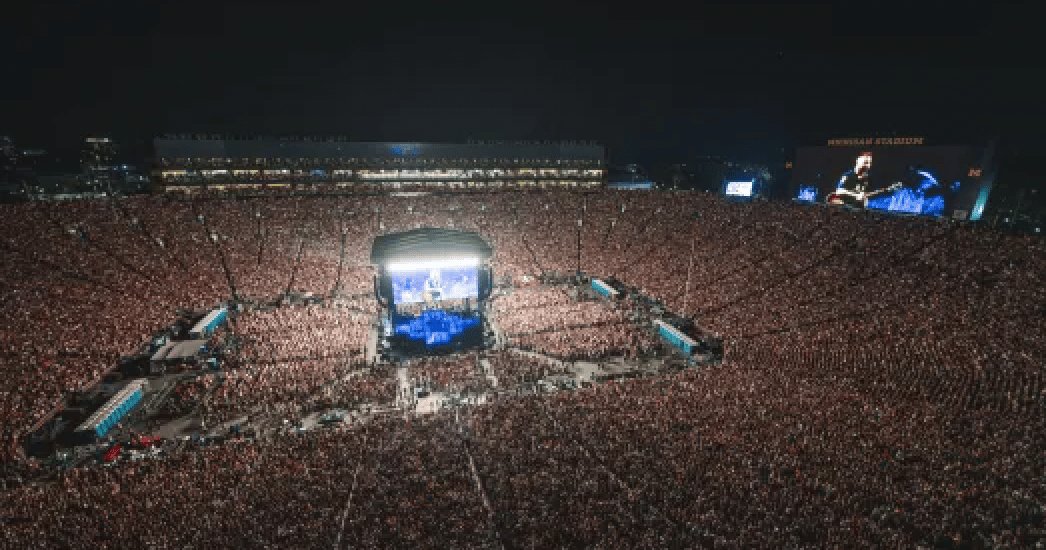

The Big House at Michigan cited above hosted its first concert this September when it hosted Zach Bryan and John Mayer. Bryan had just played at Notre Dame Stadium earlier in the month. Michigan apparently liked how it went, as Morgan Wallen is scheduled for two shows in July 2026. While U of M may have been the most storied locale to host a concert, it was far from alone. Fresno State hosted Shakira at Valley Children’s Stadium in August, Virginia Tech rocked out with Metallica in May, and the Zak Brown Band took over the University of Toledo’s Glass Bowl in May.

Seventy miles across the state, the trustees of Michigan State are set to vote on the latest redesign of the Spartan Gateway District, a mixed-use proposal that would combine athletic facilities with hotels, retail, and restaurants.

Vanderbilt recently appointed hospitality vet Markus Schreyer as the first CEO of Vanderbilt Enterprises. Its stated mission is to “explore new approaches that generate new financial resources to support Vanderbilt Athletics and the university’s broader ambitions. In announcing the venture, Chancellor Daniel Diermeier referred to the Premier League’s Manchester City. He cited their model of building commercial infrastructure around the stadium - hotels, restaurants, museums, and event spaces - that attract fan attention and dollars outside of game day.

Wake Forest is the smallest school in the ACC, which may be why it's being more ambitious about its plans. The Demon Deacons are developing a 100-acre, $250 million mixed-use district called The Grounds around its athletic venues in Winston-Salem. The project will include retail, dining, student housing, offices, and green space.

Construction is underway on Iowa State’s CyTown, where Cyclone fans will get a 30,000-seat amphitheater, a 200-room hotel, and a 15,000-square-foot food and beverage facility.

The University of Tennessee, the University of Oklahoma, and the University of Hawaii all have similar mixed–use sports/entertainment districts in the planning pipeline.

It only makes sense that venues designed to accommodate the population of entire towns that sit idly for most of the year could be utilized more profitably. But it’s not all smooth sailing.

Northwestern University originally planned to host 12 concerts a year at its new Ryan Field after its 2026 completion date. Located in a residential area in suburban Evanston, the plan met a storm of local resistance and finally ended up squeaking through a 5-4 city council vote to allow 6 concerts. Lingering lawsuits are still working their way through the courts. As the trend continues, it can also be expected to raise already simmering issues around the tax-exempt status of schools. Technically, universities' tax-exempt status is not jeopardized by building multi-use entertainment facilities, but the income from these facilities is subject to taxation if it's from "unrelated business" activities, meaning activities not related to the university's educational mission.

It’s an increasingly fine line, however, and it adds fuel to those already complaining about their tax-free real estate holdings and lightly taxed billion-dollar endowments. Yet these obstacles are not likely to slow the trend as hungry athletic budgets need to be fed more dollars.